Living Peace 23: Letters of Wars and Peace

24. 6. 2025 | Politics

At the end of 2022, we at the Peace Institute, started organizing a series of public events entitled Thinking Peace as a response to the multitude of armed conflicts around the world. Since the world has been spiralling into dangerous global militarization, we wanted to rethink what is war, what is peace, and more importantly how to ensure a stable peace which would not be quickly engulfed in new conflicts and wars.

At the end of 2022, we at the Peace Institute, started organizing a series of public events entitled Thinking Peace as a response to the multitude of armed conflicts around the world. Since the world has been spiralling into dangerous global militarization, we wanted to rethink what is war, what is peace, and more importantly how to ensure a stable peace which would not be quickly engulfed in new conflicts and wars.

We want to expand on the Thinking Peace cycle and add new dimensions to imagining peace. With the help of amazing individuals worldwide, we are beginning a new series of public letters written by people whose lives were interrupted by war or who found themselves in a recent armed conflict. We have titled this series of letters as Living Peace to emphasize how important peace is and that people often only realize this importance when facing the brutality of war. We want to illustrate how people from Palestine, Ukraine, Rwanda, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Syria, Sudan, Afghanistan, Congo, Yemen and elsewhere think publicly about peace. How do the inhabitants of these regions face wars and military conflicts? What lessons can we learn from their intimate experiences and existential fears?

While opinions of world leaders who justify or even defend wars, dominate today’s media spheres, we want to amplify the voices that defend peace, reject violence and recognize equal rights for all. Having experienced war, they understand why it is essential to live in peace.

The 23rd letter we are publishing was written by Bave from Rojava:

We cannot claim to have lived a peaceful life because we are Kurds… Historically, we as a people have endured many massacres. I cannot separate this from my personal life, and in this way, we have collectively struggled for peace until today.

***

In that moment, we understood it was a matter of life or death. We could either defeat Daesh or let the joy we felt when the cantons of Rojava were declared free fade into a dark corner of our hearts. We were united in our struggle, and through this strengthened solidarity, we resisted. Our people gave everything they had; there was no time for sleep or rest. We would do anything. News from the front lines came in—winning or losing was measured by how many people died that day, how many survived, which villages were lost, and which were won. Kobanê became our last spark, our last hope. Our son left, joining many youths from different parts of Kurdistan to defend Kobanê.

Now we see the reality: we lost him.

***

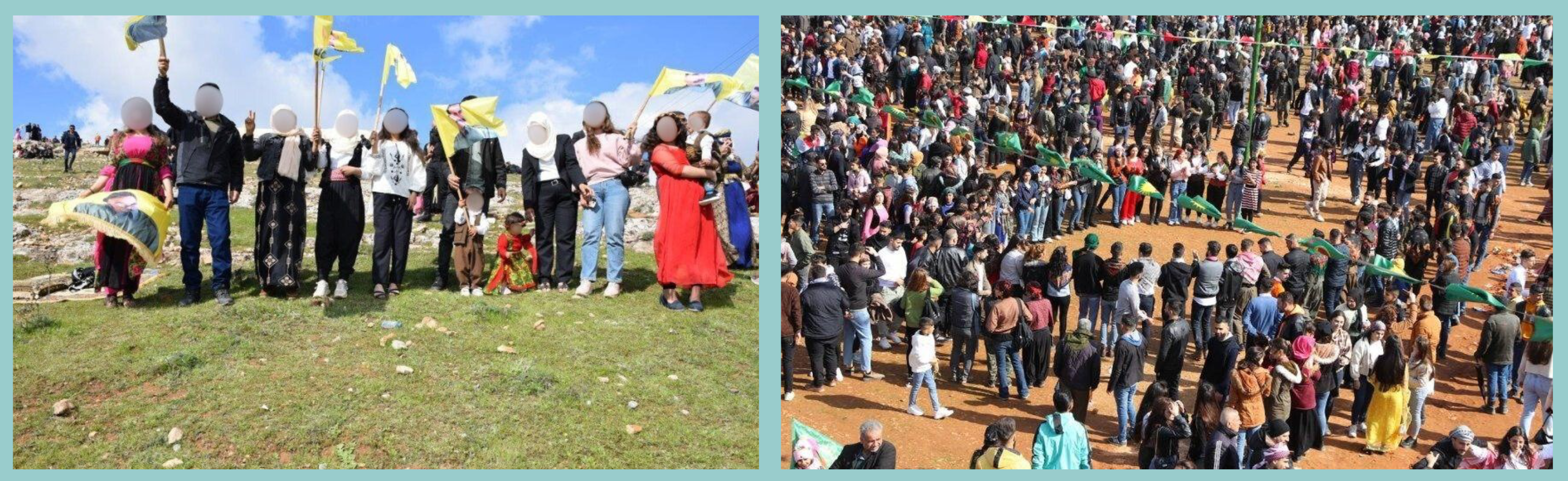

Friends rebuilt Rojava, and we are still here, striving for peace alongside Arabs, Assyrians, Armenians, Turks, and Yezidis.

We communicate in the language of peace, mutual recognition, and coexistence among peoples who have caused each other harm for far too long. We envision a system where we can live together, where everyone has a voice in decision-making. Despite the many challenges we face, we have embraced this way of life, believing it to be the solution for Syria and the broader Middle East. This is the lesson we have learned: we cannot speak of true peace until women are free and actively participate alongside us, for it is from them that we have truly learned the language of peace.

Letter by Bave from Rojava

My name is Bave Shiar. Shiar is my son, a martyr of the revolution in northeastern Syria. He fell fighting against ISIS (Daesh) in Kobanê in 2015. But I am also known as Bave Mahir, Bave Demhat, Yade Leyla, and Yade Fatma. I could continue listing names, for we are part of a collective identity, a people who have lived in unrest, always under attack.

We cannot claim to have lived a peaceful life because we are Kurds. I am Kurdish. This truth has long been unrecognized, but we know it, and we struggle for it. It meant being stopped at regime checkpoints and dragged from my car under the shadow of a cannon. It meant hearing from our neighbours that their sons had disappeared on their way home from work.

Historically, we as a people have endured many massacres. I cannot separate this from my personal life, and in this way, we have collectively struggled for peace until today.

I have lived my entire life in Qamishlo, in a small neighbourhood on the outskirts. We have family members living in Nusaybin, Istanbul, and in Germany. I cannot blame them for leaving it is not my right to do so. Those who stayed have paid a heavy price, but despite everything, we are living a beautiful life. Our neighbourhood and our city are what we know. To survive with our people, we always held onto a glimmer of hope for the movement in the mountains. They were fighting fiercely, and we were hiding them in the plains. We met clandestinely in homes at night, reading in our language, self-educating, and learning about our history—knowledge that was never taught in school.

The tensions in our country were too high, life unbearable, and the despotism of the Ba’ath regime even more oppressive. We found our opportunity in the midst of the Arab Spring, as countries collapsed around us, to become ourselves. We were prepared, yet unprepared at the same time. We took to the streets; while marching slow, our youth was fast. We embraced our roles, even though I was no longer in my twenties. We faced the ongoing war with both joy and fear. One monster was followed by the next—Daesh emerged. We were terrified, watching on TV and social media as they advanced rapidly, committing killings, rapes, and selling women. We feared for our wives, our sons, and our daughters. Self-defense became our only option.

There are many fronts in a war. Youth, both men and women, went to the front lines, organizing the resistance step by step. But it was not only military; we put our old car on the road to bring food and water, to transport supplies, and to share bread with those lighting small fires to survive the winter. There was no gasoline to heat our homes, no light except for the shining remnants of mortars and bombs.

In that moment, we understood it was a matter of life or death. We could either defeat Daesh or let the joy we felt when the cantons of Rojava were declared free fade into a dark corner of our hearts. We were united in our struggle, and through this strengthened solidarity, we resisted. Our people gave everything they had; there was no time for sleep or rest. We would do anything. News from the front lines came in—winning or losing was measured by how many people died that day, how many survived, which villages were lost, and which were won. Kobanê became our last spark, our last hope. Our son left, joining many youths from different parts of Kurdistan to defend Kobanê.

Now we see the reality: we lost him. We mourned him, burying him in the martyrs’ cemetery of Qamishlo, where hundreds walked beside us in grief. But we won freedom; we won peace. We lack the words to describe Daesh, to convey the battles fought against them, filled with horror and pain. Yet we have words to express our commitment: we will never abandon our son or all those who fell beside him. We call our revolution Soresa Şehidan, the Revolution of the Martyrs. We defeated Daesh, but Turkey continues to bomb us, having built a 700 km wall separating us from our brothers and sisters in Bakur Kurdistan.

Despite all this, we remain committed to building a new system—a democratic system that has been evolving for 13 years. The communes became our trenches, our places of meeting and decision-making. Friends rebuilt Rojava, and we are still here, striving for peace alongside Arabs, Assyrians, Armenians, Turks, and Yezidis.

We communicate in the language of peace, mutual recognition, and coexistence among peoples who have caused each other harm for far too long. We envision a system where we can live together, where everyone has a voice in decision-making. Despite the many challenges we face, we have embraced this way of life, believing it to be the solution for Syria and the broader Middle East. This is the lesson we have learned: we cannot speak of true peace until women are free and actively participate alongside us, for it is from them that we have truly learned the language of peace.