Living Peace 20: Letters of Wars and Peace

6. 6. 2025 | Politics

At the end of 2022, we at the Peace Institute, started organizing a series of public events entitled Thinking Peace as a response to the multitude of armed conflicts around the world. Since the world has been spiralling into dangerous global militarization, we wanted to rethink what is war, what is peace, and more importantly how to ensure a stable peace which would not be quickly engulfed in new conflicts and wars.

At the end of 2022, we at the Peace Institute, started organizing a series of public events entitled Thinking Peace as a response to the multitude of armed conflicts around the world. Since the world has been spiralling into dangerous global militarization, we wanted to rethink what is war, what is peace, and more importantly how to ensure a stable peace which would not be quickly engulfed in new conflicts and wars.

We want to expand on the Thinking Peace cycle and add new dimensions to imagining peace. With the help of amazing individuals worldwide, we are beginning a new series of public letters written by people whose lives were interrupted by war or who found themselves in a recent armed conflict. We have titled this series of letters as Living Peace to emphasize how important peace is and that people often only realize this importance when facing the brutality of war. We want to illustrate how people from Palestine, Ukraine, Rwanda, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Syria, Sudan, Afghanistan, Congo, Yemen and elsewhere think publicly about peace. How do the inhabitants of these regions face wars and military conflicts? What lessons can we learn from their intimate experiences and existential fears?

While opinions of world leaders who justify or even defend wars, dominate today’s media spheres, we want to amplify the voices that defend peace, reject violence and recognize equal rights for all. Having experienced war, they understand why it is essential to live in peace.

The 20th letter we are publishing was written by Boro from Bosnia and Herzegovina:

What about the young people who were born around the time the war ended, and peace came to Bosnia and Herzegovina, one might ask? These people are now at the age when they might be renting or buying their first apartment with their partners. I’d say they’re in a better position than we were. Everything is more favourable now. There are more vacant apartments; you can find them anywhere, loans are available, and so is the support from the city … Only the price per square meter has “gone through the roof.”

But, in the order of things, some things remain unchanged. Take, for example, the front pages of newspapers, of our computer or TV screens. Reading the headlines, you might think the war didn’t end thirty years ago but thirty days—or even thirty minutes—ago. Memories of mass crimes dominate, concentration camps, unpunished murders, victims without any public sympathy, mothers living alone …

In the foreground, too, are politicians who don’t just threaten with resignations but rather with a new war, or they utter sentences that cut through the fragile membrane of public opinion like a knife. I know that nothing is the same, and comparisons are unfair, but it feels almost like that joyful day when my wife, our son, and I began renovating our first apartment.

Letter written by Boro from BH:

We moved into our first apartment four months before the war started. Prior to decorating it, we had spent months renovating it. From walls and floors to doors, windows, and heating. Should I even mention the unreliable and unpredictable workers?

We moved into our first apartment four months before the war started. Prior to decorating it, we had spent months renovating it. From walls and floors to doors, windows, and heating. Should I even mention the unreliable and unpredictable workers?

We patiently endured the troubles because we knew we were building a space that would become our home. For years, we had been tenants. In socialism, that was common. Apartments for rent were only available in private houses on the outskirts of the cities. Those buildings were usually houses without facades, without heating … So we wanted to arrange the apartment the way we had dreamed of for years. Double windows, warm floors, clean airy colours.

The war started in April 1992. For months, there were signs of catastrophe, but people simply don’t have the capability to accept the destruction of faraway cities and bloody TV images as their own future.

It turned out that our apartment, while located in the city centre, was actually positioned on the front line. The line dividing the armies, which would not move for the next four years, was fixated three hundred meters from our windows. The first grenades dropped literally in front of the building’s entrance. All the window glass shattered into thousands of pieces. We inserted plastic sheets into the window frames. Everything in the interior became blurry and gray-coloured—even on clear days. When we occasionally opened the windows, the world presented its seductive charms. Flourishing greenery, birdsongs, blue skies, human voices…

Pouring through the plastic sheets were the thunder of grenades, rifle fire, and machine gun bursts, sometimes echoing in the rhythm of sporting fan chants. The electricity was gone, and we ran out of food. Panic struck, and one evening I suggested to my wife that she should leave Sarajevo with our eight-year-old son. One of the last convoys carrying civilians from the besieged city had been announced. We sat at the table. Our son was lining up his toys. My explanation was seemingly simple: “I’m a journalist, an editor of a major program—I can’t leave. All the journalists from around the world are coming here.” She listened and calmly replied: “There are only two options. We leave together or we stay together. There is no third way.”

Strangely, I felt relieved after that, even though our life has turned into a constant taming of chaos. No electricity? Use a glass full of oil and dip in a shoelace. No water? There is a spring rain and a nail to punch a hole in the gutter, about a meter above the sidewalk. You wouldn’t believe how fast you can fill a bathtub. Or you take canisters, walk ten kilometres, and fill them with water at the brewery’s century-old wells—if you survive the trip. No food? There is always a substitute for everything. Hunger is also a solution.

One day I was wounded. I was traveling with about twenty radio-television co-workers toward the city. We were all crammed into a vehicle that, under normal circumstances, could hold eight people. At one point, as the van sped along the main road, the side window shattered, and everyone instinctively turned toward me. My jacket had bloomed open at the back. I turned to the others and asked in disbelief, “Did it hit me?” Everyone nodded sympathetically. A grenade had exploded about a hundred meters away, and a piece of shrapnel had travelled far, smashed the glass, and lodged in my back. It even pierced my thick jacket, which slowed it down further. The wound took months to heal. I still have a decent scar. Recently, while I was getting a dental X-ray, the technician asked me, “What’s this in your upper back? Some piece of metal?” I didn’t even know the shrapnel was still in my body. It’ll die with me.

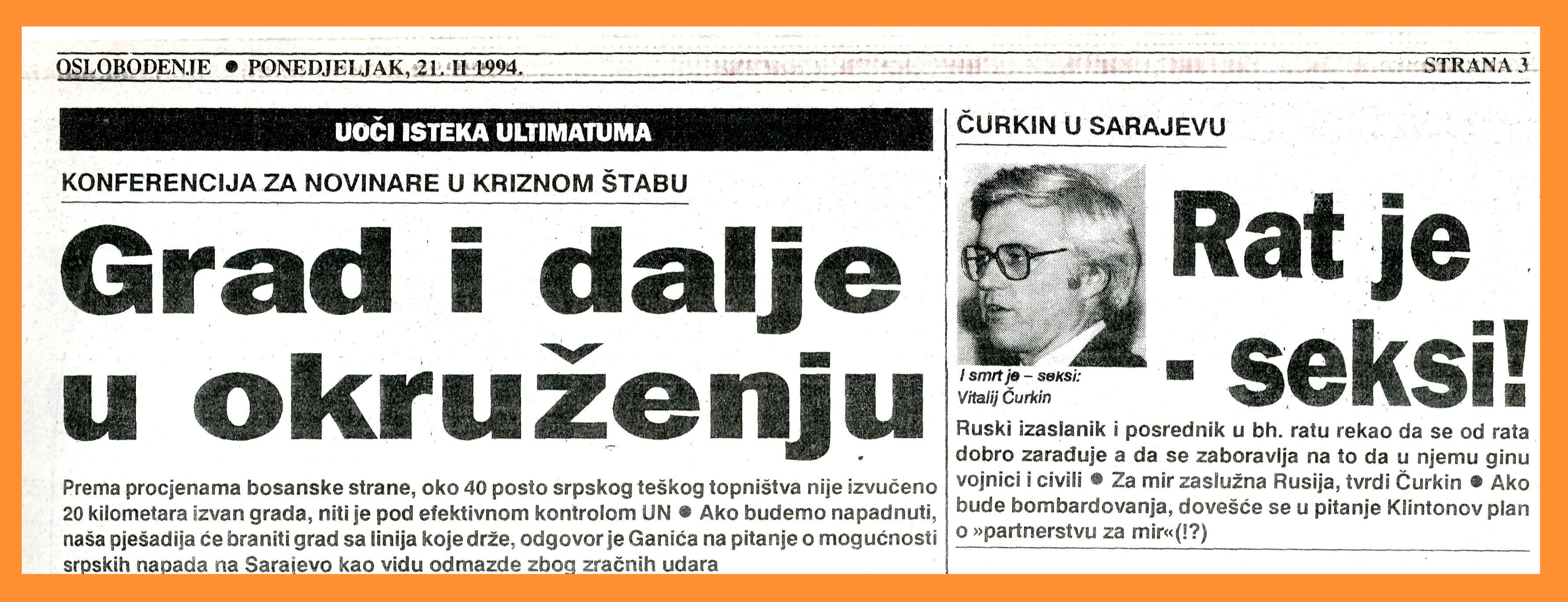

I started reporting for the Voice of America. One of the first assignments was a press conference with Vitaly Churkin, Deputy Foreign Minister of Russia. The Russians had remained absent from the Bosnian conflict for the first two years of the war. Preoccupied with internal problems and their dulled leader Yeltsin, they were invited in late February 1994 so that the Bosnian Serbs would readily accept the looming NATO ultimatum. The Serbs had to withdraw their heavy artillery twenty kilometres away from Sarajevo under threat of air strikes. A mortar shell fired from Serb positions at the Markale market in the city centre precipitated this withdrawal. Sixty-eight people were killed, nearly two hundred were wounded. And that woke up the West.

So, Vitaly Churkin arrived. For the Serbs to accept the NATO ultimatum, the decisive factor was the announced arrival of Russian troops in Bosnia. Politicians in Sarajevo consoled themselves that “the arrival of the Russians wasn’t because of the Serbs, but due to American support for Yeltsin so he could silence his domestic opponents.” Some media claimed that this made Sarajevo the new Berlin. The city now hosted British, French, and Russian troops—only the Americans and the wall were missing.

Only the politicians seemed satisfied. NATO Secretary General Manfred Wörner welcomed the role of Russia: “especially in the final phase when they helped us achieve this result.” The Russian soldiers, who entered Bosnia for the first time on February 21, 1994, were welcomed with a public celebration in Pale, the wartime headquarters of Serb politicians. An ox was roasting on a spit, bread and salt were offered, and elders handed their children to the Russian soldiers on armoured vehicles. The Russian soldiers returned the affection. From time to time, they flashed three fingers—the Serbian symbol—to the ecstatic crowd. One local newspaper noticed Belgrade writer Momo Kapor at the Russian greeting. They published his conversation with some local boys: “Why do you love the Russians?” uncle Momo asked. “Because they’re on our side,” they all replied in unison.

Wrapping up his political meetings in Sarajevo, Churkin conversed with a group of journalists in February 1994. At the end of the diplomatic segment, to everyone’s shock, he philosophized about the order of things in the world. He literally said: “War is sexy. War is where journalists build careers and generals earn ranks. Diplomats make money and their names in wars, while soldiers and civilians lose their lives.”

The war continued for another year and a half. Our apartment was so devastated that, right after the peace agreement, we began renovating it. The first thing we did was replace the windows and repaint the walls. They were black from soot because we had a stove in the middle of the living room during winter. After four years of interruptions and studying in a basement, our son started sixth grade. Almost all our pre-war friends were gone.

Twenty years after his Sarajevo meeting with journalists, Vitaly Churkin died. A sudden heart attack, they said. He died in New York, as Russia’s permanent ambassador to the United Nations. Most of the political and military figures who graced the front pages during the Bosnian war have either died or been convicted of war crimes. Or both. At the same time, they are now top candidates to have streets and squares named after them in Bosnian cities. The Bosnian Serbs immediately erected a stone plaque for Churkin and announced a monument in the part of Sarajevo they had conquered during the war.

What about the young people who were born around the time the war ended, and peace came to Bosnia and Herzegovina, one might ask? These people are now at the age when they might be renting or buying their first apartment with their partners. I’d say they’re in a better position than we were. Everything is more favourable now. There are more vacant apartments; you can find them anywhere, loans are available, and so is the support from the city … Only the price per square meter has “gone through the roof.”

But, in the order of things, some things remain unchanged. Take, for example, the front pages of newspapers, of our computer or TV screens. Reading the headlines, you might think the war didn’t end thirty years ago but thirty days—or even thirty minutes—ago. Memories of mass crimes dominate, concentration camps, unpunished murders, victims without any public sympathy, mothers living alone …

In the foreground, too, are politicians who don’t just threaten with resignations but rather with a new war, or they utter sentences that cut through the fragile membrane of public opinion like a knife. I know that nothing is the same, and comparisons are unfair, but it feels almost like that joyful day when my wife, our son, and I began renovating our first apartment.