Living Peace 18: Letters of Wars and Peace

14. 5. 2025 | Politics

At the end of 2022, we at the Peace Institute, started organizing a series of public events entitled Thinking Peace as a response to the multitude of armed conflicts around the world. Since the world has been spiralling into dangerous global militarization, we wanted to rethink what is war, what is peace, and more importantly how to ensure a stable peace which would not be quickly engulfed in new conflicts and wars.

At the end of 2022, we at the Peace Institute, started organizing a series of public events entitled Thinking Peace as a response to the multitude of armed conflicts around the world. Since the world has been spiralling into dangerous global militarization, we wanted to rethink what is war, what is peace, and more importantly how to ensure a stable peace which would not be quickly engulfed in new conflicts and wars.

We want to expand on the Thinking Peace cycle and add new dimensions to imagining peace. With the help of amazing individuals worldwide, we are beginning a new series of public letters written by people whose lives were interrupted by war or who found themselves in a recent armed conflict. We have titled this series of letters as Living Peace to emphasize how important peace is and that people often only realize this importance when facing the brutality of war. We want to illustrate how people from Palestine, Ukraine, Rwanda, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Syria, Sudan, Afghanistan, Congo, Yemen and elsewhere think publicly about peace. How do the inhabitants of these regions face wars and military conflicts? What lessons can we learn from their intimate experiences and existential fears?

While opinions of world leaders who justify or even defend wars, dominate today’s media spheres, we want to amplify the voices that defend peace, reject violence and recognize equal rights for all. Having experienced war, they understand why it is essential to live in peace.

The 18th letter we are publishing was written by Laura from Colombia:

In Colombia, war is in constant change. It amazes me that there is no one alive in the country who has not experienced it and it saddens me that, despite all efforts done, it is likely that my child will know it too.

***

War has shown that women and girls suffer its consequences disproportionately compared to men. Although combatants view male civilians as targets when they think of them as aiding their enemies, women’s bodies are viewed by parties as “war territories” (despite the objectification of feminized bodies being problematic). Women suffer sexual violence and criminal acts that their male counterparts rarely suffer. They are seen as “weaker” and —ironically— also as the foundations that sustain communities, wounding them has the potential to irreparably impact the enemy’s social fabric.

Letter by Laura from Columbia

In Colombia, war is in constant change. It amazes me that there is no one alive in the country who has not experienced it and it saddens me that, despite all efforts done, it is likely that my child will know it too.

In Colombia, war is in constant change. It amazes me that there is no one alive in the country who has not experienced it and it saddens me that, despite all efforts done, it is likely that my child will know it too.

Ever since I can remember, the sound of breaking news on TV evokes anguishing memories. The images of civilian marches asking for peace whilst the former President sat alone in a table in the middle of a demilitarized zone, embarrassed, stood up by the leader of the extinct guerrilla group FARC is now a meme, but once upon a time, it was the prelude to the beginning of the twenty first century, a period of exacerbation of violence, mainly executed by the State and its institutions.

I am now a human rights lawyer, but I was also a four-year-old girl in 1997, whose dad was a corporal in the Air Force of Colombia, growing up in the plains of the country. Sometimes, my family would travel to Bogota to visit family members. I vividly remember my mom warning me about the possibility of us getting stopped in the road by guerrilla members, hiding my dad’s military identity cards under the rubber mats of the car and asking me (in child’s play, trying to protect me) to never mention that my dad worked with planes or in uniform, but that he was a baker and made bread for a living. It was all confusing for me, but I obeyed. I wonder how many similar memories remain in other people. Later I learned that guerrillas used to practice “pescas milagrosas” in the roads of the country that connect cities, which were mass kidnappings in which the combatants took cars and people to demand money for their release.

And -although it must be said that the situation has improved greatly in the last twenty years- during the last decades of the last century, the conflict in Colombia came from all fronts: guerrillas, paramilitaries, criminal gangs and the State, all fueled by drug trafficking money.

Entering the new century, the paramilitary groups gained strength and the sound of breaking news on TV announced massacres across the country perpetrated by them, with the connivance of the State and its Armed Forces. It was impossible that, for example, hundreds of armed paramilitary men would enter a town and stay there for four days, torturing the inhabitants, looting their stores and houses, raping their women. I remember reading many years later that from February 17th to 21st, 2000, four hundred men of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC) entered the town of El Salado, staying there for days terrorizing the population (whom they accused of being guerrilla supporters). The results of that massacre were difficult to calculate for years, and to date, the exact number of dead and missing people is still unknown; there were at least sixty. This episode brought to Colombians one of the most ineffable memories of the war: the paramilitaries played soccer with the heads of many victims. Eighteen years later, I had the privilege of representing these victims before one of the transitional jurisdictions created in my country to overcome the conflict.

My personal convictions and my professional choices have given me the privilege to meet people who have lived through war and have directly been impacted by the civil conflict in the country.

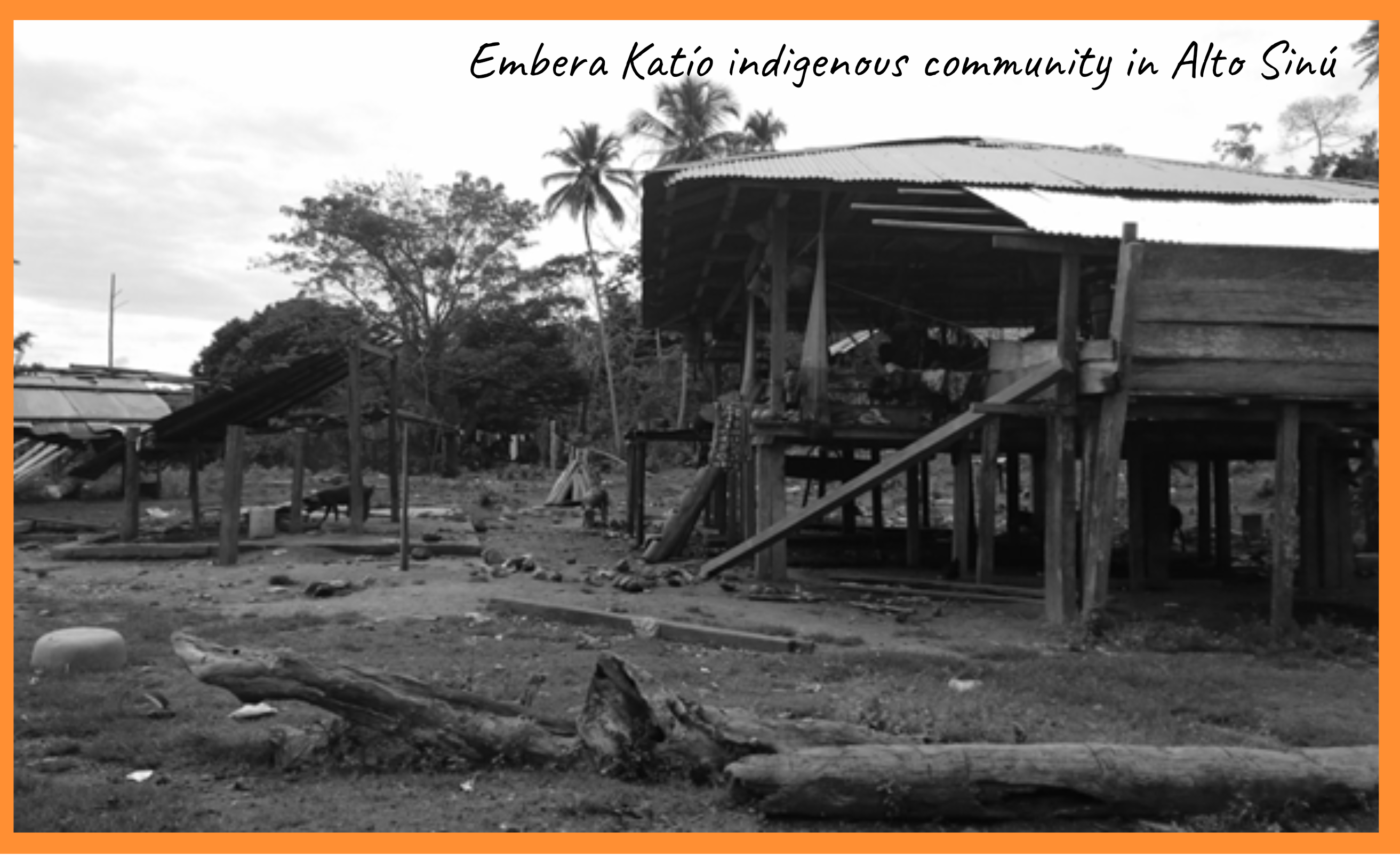

I visited the indigenous reservation of the Embera Katío indigenous community in Alto Sinú, in the Córdoba region. This area is known to be one of the birthplaces of paramilitary groups. The sacred territories of the Embera Katío and their defense of their lands were an affront to the territorial advance of the paramilitaries, who labeled them “leftist defenders of the land”. Thus, the Embera suffered homicides, forced disappearances and displacements at the hands of the paramilitaries, who (sponsored by large extractive, hydroelectric, and other companies) viewed the Indigenous people as an obstacle to the region’s economic growth. To this day, after so much suffering and victimization, this community and its reservation still lack basic services such as electricity or drinking water.

I visited El Salado, a town that had seven thousand inhabitants before the massacre in 2000 and by 2018 had around a thousand people who had decided to return, having found no quality of life anywhere else. Returning to the town where they had experienced so many horrors but also called home was a bittersweet courage; their efforts to reconstruct their town’s history came with threats from paramilitary and criminal groups that had settled in the area.

Twenty-three years after the massacre, I worked with the community of El Salado again, having focused my career on defending and promoting women’s rights. Two decades later, the Colombian state still owes El Salado its debt. As in many other cases, the State’s has only manifested itself through the militarization of the area. The presence of military personnel has brought new problems of victimization, such as armed adult soldiers with power (symbolic or real) over the population establishing so called “romantic relationships” with girls, in some cases as young as twelve years old (creating abusive relationships that generate new and greater cycles of exploitation and violence for women and girls in an already over-victimized community).

War has shown that women and girls suffer its consequences disproportionately compared to men. Although combatants view male civilians as targets when they think of them as aiding their enemies, women’s bodies are viewed by parties as “war territories” (despite the objectification of feminized bodies being problematic). Women suffer sexual violence and criminal acts that their male counterparts rarely suffer. They are seen as “weaker” and —ironically— also as the foundations that sustain communities, wounding them has the potential to irreparably impact the enemy’s social fabric.

With everything, Colombians keep moving forward, rebuilding, learning. For the first time in our country’s history, we elected a leftist president in 2022, the first to survive the elections. Colombia is now one of the countries with the most stable economies in Latin America and, although there is still much progress to be made, our resilience keeps us going.